Change Starts with a $6 Soccer Ball

The World Cup is underway, so I thought I would share a few soccer stories from around the world from my reporting involving the beautiful game.

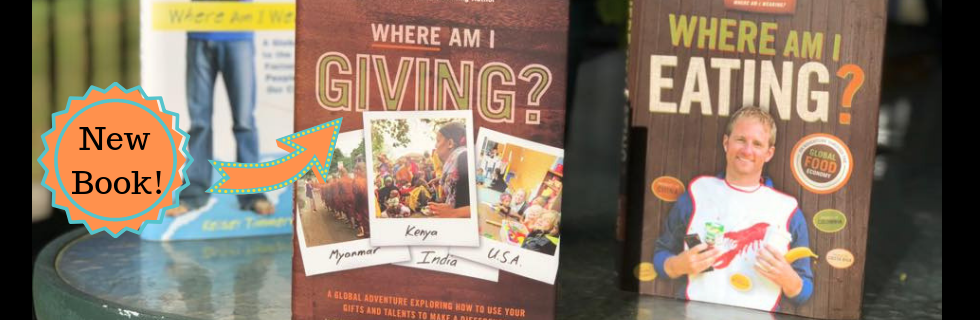

In India, I got to spend time with Ashok Rathod, who founded the OSCAR Foundation. I wrote two chapters in my book Where Am I Giving? on my experiences in Ashok’s community. In the chapter below I meet Ashok and learn how he’s impacting his community through soccer.

If you like what you read, consider following OSCAR on Facebook and consider buying a copy of Where Am I Giving? for more stories of awesome givers like Ashok.

Buy Where Am I Giving? at Bookshop / Indiebound / Barnes & Noble /Books-A-Million / Amazon

Chapter 16: Start With Your Local (India, 2017)

Crossing caste lines / Towers & slums / Untouchables

WHEN THE 50-SOMETHING-YEAR-OLD MUSTACHED man wearing a sailor’s suit saluted me, I wasn’t comfortable. Nor was I when the hotel manager told me the man in the sailor’s suit, his “boy,” could carry my bag to my room and then called for him: “Boy!”

I wasn’t comfortable ringing a bell at lunch so a waiter could meet my immediate need – Heinz ketchup.

I wasn’t comfortable when the man in the sailor’s suit saluted me as I left in the morning to make my way to the docks. I’ve earned no rank or status. I had enough money to buy a plane ticket to India. I was American. I knew a guy who knew a guy who was a member at the Royal Bombay Yacht Club and could get me into one of the three-room guestrooms accessed by a palatial staircase or a steam-punk elevator. None of which made me salute-worthy.

The man’s spine straightened, and his heels nearly clicked. I awkwardly nodded to his salute and flagged down one of Mumbai’s famous black-and-yellow cabs. To my relief, the driver turned on his meter. The day before a driver had refused to do so, intending to charge me more than the going rate, and I demanded he stop to let me out, but he wouldn’t. I demanded to be treated equally—like a local. Why should I pay more? Why should I be treated differently? I had threatened to jump out, had my door open and everything. He called my bluff. I wasn’t going to jump out of a moving car because of $1.

The driver dropped me at the Sassoon dock. This wasn’t a dock for yachts, but one of the oldest docks and largest fishing markets in Mumbai.

The women who lined the entrance of the dock didn’t salute me; they motioned to the fresh catch before them: Would I like to buy a recently killed stingray?

It was tempting, but I was heading to a meeting that a dead stingray would make awkward.

At the dock, men tossed faded pastel baskets filled with their catch eight feet up to other men standing on the seawall. Those men passed the catch to other men who auctioned the fish to women. Auction winners walked away with shrimp, crab, and fish of all sorts balancing on their heads. They pushed me out of their way to get where they were going.

Ashok Rathod rolled up on his scooter. He wore prescription Oakley glasses and had disheveled, thick hair, and a look on his face that seemed to question everything. We wove our way through the crowds at the dock.

“Sometimes the women will pour fish water on you to get you out of the way,” Ashok warned in a gravelly voice. Ashok is the founder of the OSCAR Foundation. He’s a movie lover and named the nonprofit after the Oscar awards, which was somewhat incongruent with the organization’s mission and perhaps in violation of copyright, so he came up with an acronym: Organization for Social Change Awareness and Responsibility. Ashok chose to meet at the dock to tell me about OSCAR’s work using soccer as a means to promote education and empower underprivileged kids.

“I started working here when I was 10,” Ashok said.

Ashok’s father worked on the docks for 35 years before becoming a gardener. He did not want his children to follow in his footsteps, so he enrolled them in a government school where the teacher-to-student ratio was 1 to 65.

“The education is not good,” Ashok said. “One day we decided during our break to go to the fishing market to see how our parents made money. There were a lot of fish on the floor. Everyone was busy running around to sell fish, buy fish . . . Whatever fish fell down, we were collecting and putting in a bucket. When the bucket was full, someone came to us: ‘How much?’”

Back then, 17 years ago, fish were so plentiful that no one cared about the small fish; now the adults collect them. Things were cheaper, too. Ashok could go to school in the morning, sneak off to the fish market at lunch to earn $2 or $3, and head back to school with enough money to see a movie and grab something to eat.

“One day my father found that I was here working. He warned me, ‘If you come again, we will throw you out of the house.’ So I stopped coming because if I got thrown out of the house, where would I stay?”

Ashok stayed in school, while his friends dropped out to work.

We walked past the boats to a long open-walled building beyond the hustle where men repaired fishing nets. During the monsoon, the government doesn’t allow large-scale fishing. During the main season, this dock would be full.

By age 15, Ashok’s friends started drinking, gambling, and smoking. They broke into groups sort of like gangs and got into fights with other groups. When their parents found out what their boys were up to, they made them marry. The responsibilities of a family would calm them down. This was the cycle of life in the slum. Few went to school. Few left.

“Now they are 28 or 29 years old and have two to four children,” Ashok said, watching the men fix the nets. “Now everything becomes expensive and their income is less . . . They have to work 12 hours. It’s a hard life for them to feed their children. I’m sharing this story because I wanted to become like them: to earn money, enjoy life and not to think about the future, to think of today’s life and enjoy. I thought this was the best way. But because of my father, I continued school.”

A white police SUV pulled in front of us, blocking our path to the end of the dock. The police called Ashok over to check out what we were doing. In November 2008, 10 terrorists came ashore on the Sassoon dock and executed four days of shootings in a train station, café, hospital, movie theater, and hotel that claimed 164 lives. The fishermen had been reporting their concerns about strange and unlicensed boats around the docks for days leading up to the attack, but no one listened to them – they were just fishermen.

The police are determined not to make the same mistake again and are extra sensitive to a foreigner walking around snapping photos and taking notes. Ashok and I walked in silence and once the police drove out of sight, I asked him to continue his story.

Ashok graduated and volunteered with Door Step School, a nonprofit that worked to educate kids with the goal of enrolling them in public schools. A few years later, he got his first job with another NGO, Magic Bus, which also focused on educating kids.

“One day I was coming home from work and I saw two boys from my neighborhood. They were smoking at the age of 13. They saw me, and they hid behind a car.”

The kids were on the same path as his friends, the same path he would’ve taken if not for his father. Ashok had a vague idea of doing something to help kids in his own community.

“I identified 18 children who were school dropouts and I asked them, ‘Do you want to play football?’ I didn’t tell them anything about education directly.”

The kids mostly played cricket, but they were interested in football – or as we refer to it in the U.S., soccer. They had never worked with a coach in any sport before and the prospect of having a coach and playing a sport more formally appealed to them. Ashok told them to come to the field Saturday at 4 p.m. They did, all 18. Ashok didn’t think any of them would show up, so he didn’t go.

“They called me: ‘Where are you? We are here to play football!’ I said, ‘Wait, wait, I am coming. I reached there in 10 minutes.”

The kids saw him coming, empty-handed. He didn’t even have a ball. “Some football coach,” the kids thought. He led them in a few other games and promised he would return the following week. He couldn’t really afford a ball, but bought one anyway, for $6 – a quarter of his weekly salary.

“Initially,” Ashok said, “they weren’t willing to play each other because they were coming from different castes and religions. Everyone wanted to keep the football with them, and nobody wanted to share.”

Ashok decided to mix the teams, and soon the kids were celebrating goals across castes and religions. “Basically,” Ashok said, “it’s about all cultures and religions living together. It’s about unity.”

He told them that if they wanted to continue, they had to enroll and stay in school. Ashok was onto something.

More kids started to show up, which was great, but a problem because he couldn’t afford more equipment. Fast-forward 10 years, and the OSCAR Foundation now reaches 3,000 kids. Prince William and Kate Middleton have visited. Manchester United forward Juan Mata spent two days practicing with the kids and, no doubt, getting a similar tour that ended in the same improbable location: Ashok’s home.

We made our way from the dock to Ashok’s community. I sat on the back of his scooter as the monsoon season pelted us with rain from a gray sky. The Ambedkar Nagar slum in Cuffe Parade sits off the road behind a high wall painted with OSCAR Foundation art: a painting of kids raising their hands and a close-up of a girl’s face.

“That is the raising hand,” Ashok said, pointing to the paintings, “like coming up and also having an opportunity to help others come up. This is about women and girls. They have many challenges, but they are strong and face them. Forty percent of the kids in our programs are girls.”

Ashok led me past the wall and down a crooked alley. Nothing was straight. The walls of the houses weren’t. The ground was uneven. For the most part these weren’t the tin shanties and tarps that I had come to know in the slums of Kenya or Cambodia, but two-story structures carved out of a world of concrete. Local media outlets referred to them as “hutments.” The first levels housed stores, and steep ladders accessed the dwellings above.

We passed kids in red OSCAR shirts. They asked me if I played football, probably hoping I was some less athletic European star they didn’t recognize. Another kid asked me if I knew Juan Mata.

“Here they are mostly working in laundry,” Ashok said.

A man swung a long white sheet across his shoulder and then whipped it down like a hammer at a carnival trying to ring a bell. An arch of water followed the tail of the sheet.

Ashok estimated that 15% to 20% of people in his community beat, scrubbed, and dried the laundry of the area hotels and the surrounding luxury apartments.

“From my hotel?” I asked, as if it mattered. Should I have more empathy or guilt or connection with this man if it were my sheet?

A man, wearing only a bleached white towel, stepped to the side as we left the laundry. He brushed his teeth, white foam gathering in the corners of his mouth.

The alley narrowed. I felt like a giant, my shoulders barely clearing the distance between buildings. Ashok climbed a ladder.

“This is the library,” Ashok said.

Shelves on the walls held short stacks of books organized by grade level. There was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, a Hardy Boys graphic novel, The Story of India for Children, and the somewhat creepy title of Crazy Times with Uncle Ken. A cartoon frog and dinosaur were painted on the wall along with the phrase: “Send them to school.”

Two office chairs sat at a desk where Ashok put his wallet stuffed so full of cards that it was round – the wallet of a man who won’t let go or is too busy to bother. Other than that, the middle of the room was open. It might’ve been 10 feet across at the most. Ashok told me that most homes in his community were smaller than this room and slept six or seven people.

I asked if he lived in a similar place, thinking that he probably didn’t, thinking his education had lifted him to a higher standard of living, thinking that the founder of a nonprofit that had been visited by stars and princes – and who had earned the support of embassies and corporations – would live elsewhere.

“Yes,” Ashok said. He reached into a cupboard and pulled out a small bedroll. “This is my bed. I sleep here.”

His phone rang. He apologized and answered it.

I looked around the room and out the short doorway. A shining apartment tower seemed to rise into infinity. Archana, the woman who first told me about Ashok and OSCAR, lived in that apartment tower. She was a friend of the man who got me into the Royal Bombay Yacht Club.

Ashok can roll out his bed on the floor and see the tower where a three-bedroom, 2,000-square-foot apartment lists for more than $2 million. When the sun rises, the shadows of the towers, the most desired real estate in Mumbai, reach toward the slum.

A month before my visit, the Forest Department, accompanied by 100 police of officers, bulldozed more than 1,000 homes here. They claimed the homes were in violation of a law protecting mangrove cover. Residents claimed that the demolitions took place without notice, and they weren’t allowed to save their belongings beforehand. They speculate that someday their homes will become new high-rises.

Residents of the slum work in the apartment towers as domestic help and drivers. They cook exotic meals they would never eat from countries they will never visit. They pick up toys they could never afford and support lifestyles they could never live.

It’s not normal for someone in the apartment tower with ocean views to go down and visit the slum. Arachna first visited five years ago when her staff invited her to their homes during Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights. Now she volunteers as an English teacher and, collects toys for OSCAR’s community toy library. Sometimes she takes the kids to the movies on their birthdays. She has arranged for a Santa to go door-to-door delivering chocolates in the community. She inspired a friend of hers to donate his services for a dental clinic.

“Ashok is super inspiring,” she told me. “He’s giving back, not from a higher place, but from where he lives. He’s stayed inside the slum even though he could leave.”

The world has haves and have-nots, but the proximity – a short walk – and the disparity between the apartments and the slum are staggering. Yet, many who live in the apartments choose not to experience the slum even though they have a “slum view” every bit as much as they have an “ocean view.”

People in the towers think the men are drunks, that the slum is dirty. They have strong opinions about a place they’ve never been. They may like their help, see giving to them as their charity, and see them as part of their family, but not extend that charity, empathy, or love to the other residents of the slum.

In India those who believe in karma believe that those who live in hutments got what they deserved. Archana told me she believed in karma, but she also believed in the importance of spending time supporting OSCAR and interacting with people in the community.

Ashok inspired her, and she inspired her friends to give, although not all of them are comfortable visiting. She sees herself as a bridge.

Ashok hung up the phone. It was his girlfriend. Speaking of divides and bridges, she’s from another caste. She’s getting a Master’s in women empowerment at one of the best schools in the country. He’s Banjara and she’s Brahmin. His parents just found out about the relationship and don’t approve. They are afraid he will leave. Her parents don’t even know. They met five years ago when he was speaking at a conference she attended.

“I’m from a very low caste,” Ashok said. “I don’t believe in caste. According to [society] I come from the very bottom and she comes from the top.”

In some states in India, the government classifies Banjara as an “other backward class” (OBC), a term referring to castes that are socially and educationally disadvantaged. Sometimes they are referred to as “untouchables.”

The Brahmin occupy the top of the social structure. In Hinduism they are seen as the priests and protectors, the closest to the gods.

Ashok and his girlfriend come from different cultures and speak different languages.

People in the community look up to Ashok. He has received awards on TV and appeared alongside global celebrities, and more than that he has promoted education and unity. Kids are going to university; they are traveling abroad. Gang membership has declined. He has inspired other sports programs in the community. People greet him as a celebrity, but not some unknowable celebrity. He’s their celebrity.

“Now the community is going against me,” Ashok said. “People are against the relationship. Because they think that here I am a famous face for the youth and the children, and they think if I get married to a different caste, other youths will also follow me.”

Ashok intends to marry his girlfriend, but he worries what that will mean for his family and the community he loves. Someone had already totaled his old scooter by beating it with a heavy rock. I could hear the pressure in his voice. It wasn’t really a decision anymore. He knew what he would do. He just couldn’t predict the impact that leaving would make.

“I will leave,” Ashok said. “I love staying here, but, yes, I want to leave.”

Two years into OSCAR, he struggled with the kids’ parents. They weren’t happy. The kids were always using practice as an excuse to run off. Eight of the kids dropped out of school.

Some of the parents weren’t sold on the idea of school. Unlike Ashok’s dad, they didn’t see the value of an education. For generations, there were set jobs for set castes. Their children would do laundry, or fish, or work in a home, or drive a car. This perception remained, despite the fact that social mobility in India – the percentage of the population escaping poverty – has been equal to that in the United States for more than a decade.

When Ashok started the program, no one gave him money. They thought he might misuse it.

“They were judging me because I live in a slum,” he said. “Then one day in 2009, I shared this problem with the children.”

The OSCAR team had lost in the semifinals of a tournament. The kids were devastated. They cried. Ashok started to give them a pep talk and started to cry himself. His team had lost to teams that had more equipment than his kids had. He felt that he had let them down. He walked out of the room, wiped away his tears, and then returned.

“Competition isn’t easy,” he told them. “Anything you want . . . you have to work hard. Practice. Practice. Practice and work hard. This time we reached the semifinal; next time we can reach the final. It’s not your mistake that we don’t have equipment. If we had more equipment your game could improve faster. Because I don’t have money, I can’t buy more equipment.”

What had started as a pep talk devolved into exposing the depressing truths that had brought tears to Ashok’s eyes in the first place. No one believed in Ashok enough to give him money – no one except for the kids.

They had a solution. Every kid who participated in OSCAR would bring a single rupee (less than 2 cents) to each practice. Ashok used the money to fix the discarded balls from other teams, which cost him less than a dollar. He had more equipment for more kids. OSCAR’s first major financial backers were the children themselves.

That was the tipping point. By 2014, OSCAR was working with 600 kids, and in 2017 with 3,000 kids.

OSCAR has grown to other communities and states in India.

***

I accompanied Ashok into a neighborhood interested in starting a program with OSCAR.

The flat, muddy, clay field looked like the blank slate of a future high-rise apartment building. Trump Tower Mumbai, still under construction, looked down upon us. I had seen a billboard advertising the $1.2 million condos that read: “Any resemblance to a 7-star hotel is purely intentional.”

The property’s website has a section on privileges, which included: “A private jet at your service: Chauffeur-driven cars are passé. As a resident of Trump Tower Mumbai, you have a private jet at your disposal, ready to whisk you away to a destination of your choice. This service is the ultimate way to travel. But then our residents are used to being spoiled.”

Other privileges included a Trump Card that will allow you to “live without boundaries, limits or compromises” and stay in other Trump properties around the world, a pool where you can “soak up the luxury . . . located high above the ground, for your pleasure.”

Far below, we were standing in monsoon mud puddles. A Cummings generator hummed rather quietly, powering a welder renovating the stands. Orlando, OSCAR’s newly-hired program manager, talked to me over the hum. He was as tall as I was; his hair was shaved on the sides and curly on top. If someone had told me that he was a famous Indian soccer player, I would have believed it. He was well educated and came from a family of means. Previously he had worked in a call center and talked to English speakers all over the world.

A man in his forties arrived. He talked with Ashok and then made a call. Soon 12 college-aged students showed up, each of them with unique boy band hair – thick, coiffed, styled.

Introductions were made, and first they determined what language was best to use for everyone: Hindi.

Ashok mentioned the successes of the program, the kids, Juan Mata, and the awards. The students started to look from Ashok to one another, nodding their approval and sharing looks that said: “This is pretty cool. We should do this.” But then their body language shifted when they realized they were too old to participate as athletes in the program.

Ashok won them back when he talked about the young leaders program. There were 150 active young leaders in OSCAR, led by eight staff coaches.

Behind them, a laborer stacked bricks in a wheelbarrow with a wheel that made a clunking noise once every revolution. Ashok talked of a world of opportunities beyond the field, beyond Trump Tower. OSCAR students were going to England; they were going to visit Manchester United.

As Ashok spoke, the group grew. People just appeared. By the time Ashok was finished speaking there were 20 potential coaches and players passing him their names and phone numbers.

At the end of the meeting when participants divided themselves into smaller circles, Ashok walked over to a group of kids playing cricket. He doesn’t walk with the natural step of an athlete. His feet duck out a bit and he shifts from side to side in a strut. His glasses are thick, and he’s short. If this were a movie, Orlando would be the leading man and Ashok his sidekick.

Ashok held a soccer ball in his hands. He offered the ball to the kids.

“We say that football is our religion,” Ashok told me. “Football never tells you, ‘Don’t pick me because you are a Christian. Don’t pick me because you are a Hindu or Muslim.’”

—

That night I returned to the Royal Bombay Yacht Club to a world where a man in a sailor’s suit saluted me, where my five nights cost more than a year’s worth of rent in the slum, where a locker room attendant gave me fresh bleached white towels and mouthwash. It felt like I was in a tower of privilege looking out at the ocean view as if it were mine, something I earned or deserved. In India the haves and have-nots are in sight of one another if they take the time to see.

Part of me wants to enjoy the view, looking out and not down, but mostly I don’t want to forget seeing the tower from the slum.

The lives of those in the towers and at the yacht club are closer to my own, and probably yours, than to Ashok’s and the OSCAR kids. I have lived in a yacht club most of my life, really. If I feel uncomfortable at the yacht club, I should feel uncomfortable in my own life, unless I do something about it.

In the tower a soccer ball is just a soccer ball. But in the Ambedkar Nagar slum, a soccer ball is much, much more.

If you like what you read, consider following OSCAR on Facebook and consider buying a copy of Where Am I Giving? at Bookshop / Indiebound / Barnes & Noble /Books-A-Million / Amazon

Highly recommended did this. Very interesting information. Thanks for sharing!

https://www.okbetsports.ph