Election Day in Kenya

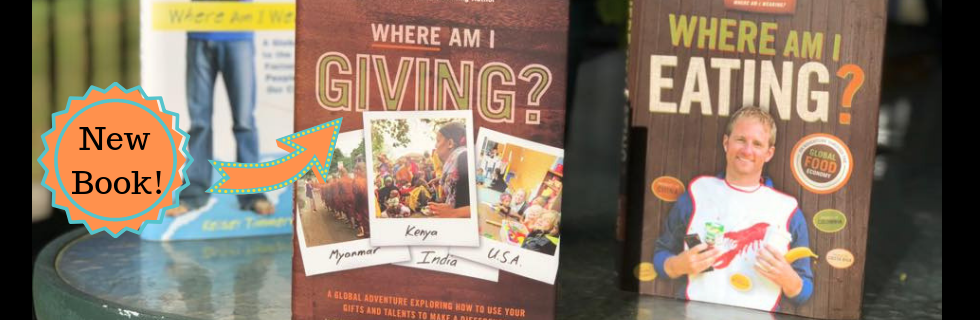

Today is election day in Kenya. Presidential elections are sometimes violent and chaotic in Kenya (in the United States, now, too). I was in Kenya for the 2017 elections and thought I’d share an excerpt from my book Where Am I Giving? about what that was like.

***

Mom thought we were being abducted. But it was worse than that.

Her flight landed in Nairobi at the absolute worst time of the last 10 years. After days of contention in the presidential race, the election commission had declared incumbent, Joseph Kenyatta the winner. Nairobi had essentially been closed since the election—stores were boarded up and the streets of a city with 3 million people were empty. The few times I had ventured out it felt like the excitement and anticipation of Christmas met the hesitation and fear of a zombie apocalypse.

For Mom’s sake, I tried to act like I wasn’t afraid and made small talk about inflight movies and how serious London airport security took liquids left in your luggage. I looked at the crappy car’s fuel gauge buried on E as the driver pulled into another gas station.

Mom thought that he was looking for someone to meet up with at the gas station to pass us on into some tourist trafficking ring. But I sensed his fear and Mom sensed mine. All the stations were closed. There were no other cabs, no cars, no one.

Residents of the slums supported the challenger, Raila Odinaga, and any news about the results led to violence spilling out onto the streets. Reports of gunshots and roadblocks were already filling up social media channels. There were protestors on the street, legitimately protesting elections results that would be overturned and later reaffirmed, and there were those who took advantage of the chaos to loot and create their own justice and injustice. I hated to even think about what would happen to our car and us if our car ran out of gas in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“Welcome to Kenya! Welcome to Africa!” I told mom, still trying to convince her and myself that everything was cool.

The driver pulled into the fourth closed gas station before giving up and making a go for our hotel.

What kind of an idiot doesn’t start this night, of all nights, with a full tank?

If he ran out of gas, I was going to kill him myself, but we made it.

He dropped us at our hotel behind a guarded gate and drove back into the night. It was only then that I started to feel any compassion for the driver. I hoped he made it back.

To calm our nerves, Mom and I each had a Tusker beer at the outdoor bar. That was when the gunshots began.

It was like a reverse PTSD. The sound of fireworks made me happy, and then the realization that they weren’t fireworks scared me. The shots sounded close. At first they popped with the frequency of an Independence Day’s grand finale or a war zone and then tailed off into a shot here and there and then silence.

“I’ll take the first watch,” I told Mom, when we made it back to our room. That’s something I always wanted to say, something the tough guys in the movies who can fight off terrible things in the night say. But it’s not so cool, when you mean it.

At 2AM a shot closer than all the rest—seemingly just outside the wall of our hotel—slammed into something. I put my shoes on and got ready for whatever. I’ve heard gunshots. I live in rural Indiana and my neighbors seem to have an arsenal, but the thunder of a shot has different meaning when you know they aren’t directed at a target but at a person. And then there was silence. No sirens. No yells. Dead silence.

The police had shot someone at our gate. I was conflicted how to feel about that. I had spent the last week with people who feared the police.

I told Mom to go back to sleep as I peeked through the curtains of our first floor cabin. I sat still and focused my hearing out into the night beyond the walls searching for threats on the edge of reality and imagination.

At 4AM the front gate squeaked open. Here they come, I thought.

I peeked through the curtain, my heart racing.

Mom sat up. “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing. I heard the gate. Wait . . . there are people walking this way!” I yell whispered.

I went to a different window not because there was a better perspective, but simply because I was full of nervous energy and had no idea what to do. Eyes. Throat. Groin. I was prepared to go for all the places you weren’t supposed to go for in my college Kung Fu class. A man dressed all in black was waving his arms as he walked next to another man.

Here they come!

I recognized the guy as a fellow guest, walking next to a security guard. I was awake the rest of the night.

I’ve rarely felt more afraid, trapped, and exposed to the violence of the world than I did sitting in that hotel behind high walls with electric fencing and a guard.

The night was just a small taste of what daily life was life for many, including the friends I had spent time with leading up to the election who lived in the slums.

Their night and the days following were much different.

“We are safe, Kelsey, and forced to stay indoors during the night,” texted Rozy Mbone, the leader of a group known as the Legend of Kenya that promotes peace in the slums. “So far one man was killed by hungry mob who were supporting Raila. Criminals also took advantage of looting and breaking into people’s shops. One of our member has been shot dead.”

Others sent me pictures through WhatsApp of people beaten, shot, and killed in the slums. For some reason the photos would automatically populate my photo album, so a man with his brains literally on the street next to him were adjacent to a picture of my kids’ first day of school, which I had missed for this trip.

Let your voice be heard!