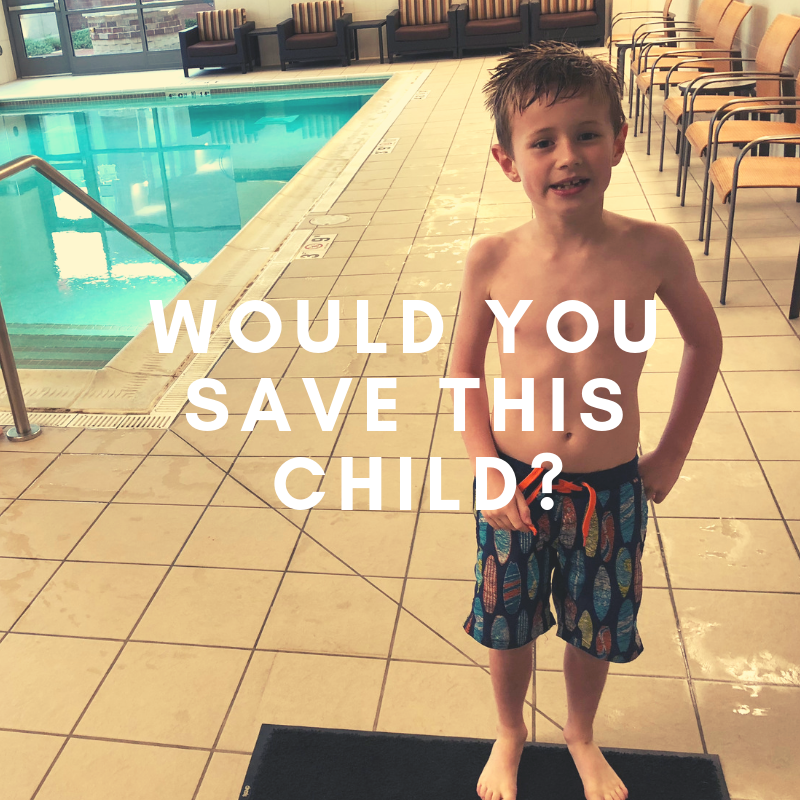

Would You Save This Child?

This is a pic of my son Griffin. I think you’d save him, if he needed saving. Why then do we ignore the preventable deaths of other children around the world when our actions would save their lives? This is a challenging question and one introduced to me by Peter Singer, author of The Life You Can Save.

This is a pic of my son Griffin. I think you’d save him, if he needed saving. Why then do we ignore the preventable deaths of other children around the world when our actions would save their lives? This is a challenging question and one introduced to me by Peter Singer, author of The Life You Can Save.

I present Singer’s thoughts in this excerpt of Where Am I Giving?:

///

I threw my cell phone, dropped my laptop bag, and ran as if my life depended on it. Part of me wanted to throw up or scream or both, but I needed to focus all of my energy on running as fast as I could.

Nothing else in my life mattered in that moment more than running.

The kids had followed me into the garage. Before I helped them into the car, I realized that I had forgotten my wallet.

Griffin, 4 at the time, is on the autism spectrum, and has a deep curiosity to explore places where he shouldn’t be — all of our cabinets, no matter how high, the top of the refrigerator, the inside of a stranger’s unlocked car, the tub of the dryer. You could say he’s part spelunker or mountain goat. In autism lingo, he’s also an “eloper.”

Here one second, gone the next.

I was pretty sure he wouldn’t bolt for the road and that I had enough time to grab my wallet off the counter and get back outside before anything bad could happen. I had assumed wrong.

Griffin wasn’t in the garage. He wasn’t playing outside the garage. He wasn’t on the swing. He usually takes two strides and does this little skip, as if he’s too footloose and fancy free to run full out, so he runs joyously. Not this time. He was running at a dead sprint down our long driveway to the road.

Dead. That’s what he would be if I didn’t get to him, I thought as I ran. But he was already two-thirds down our long driveway and I wasn’t gaining on him fast enough. The fencerow to the east of the drive would block the oncoming traffic from seeing him.

He made it to the road. I didn’t catch him in time. But luckily we live on a crumbling, country road in Indiana with very little traffic.

Griffin sat in the middle of the road and laughed. I was emotionally wrecked for three days.

Now I want you to imagine that you are standing on my driveway by the garage and you are holding your computer and phone. You see Griffin running to the road and you know he’s a kid that won’t stop. Let’s add a few certainties: 1) you’ll have to drop your phone and laptop to pursue him and they are certain to break if you do, destroying more than $1,000 of electronics; 2) there isn’t a doubt in your mind that you can catch him, but only if you drop your phone and laptop; 3) if you don’t catch him he is certain to be hit.

What do you do? Do you save Griffin?

I bet you would. I bet you wouldn’t think twice before sacrificing $1,000 of things to save a young child.

This thought experiment is one similar although not as philosophically pure as one ethicist Peter Singer put forward in his “drowning child” scenario in his essay Famine, Affluence, and Morality in 1972. In a later essay, he writes of how he uses the scenario in his classes:

To challenge my students to think about the ethics of what we owe to people in need, I ask them to imagine that their route to the university takes them past a shallow pond. One morning, I say to them, you notice a child has fallen in and appears to be drowning. To wade in and pull the child out would be easy but it will mean that you get your clothes wet and muddy, and by the time you go home and change you will have missed your first class.

I then ask the students: do you have any obligation to rescue the child? Unanimously, the students say they do. The importance of saving a child so far outweighs the cost of getting one’s clothes muddy and missing a class, that they refuse to consider it any kind of excuse for not saving the child.

He then asks his students a few more questions:

Does it matter if there are others around who could save the child but are not acting? The students agree that it doesn’t.

Does it matter if a child in similar life and death circumstance that could be prevented with your actions was in another country? The students agree that our obligation to save the child is the same: If our actions can save a life, then we ought to act.

I think most of us agree with that. But here’s where it gets challenging. Singer argues that there are children around the world who are dying preventable deaths, and most of us are doing nothing to save them. Remember that on average American’s give 2% of their income to charity and only 4% of that goes to supporting global causes. That’s less than $50 to helping save a kid’s life, or $950 less than the laptop and phone you dropped to run after Griffin.

Singer’s philosophies rooted in practical ethics formed the foundation of effective altruism, “a philosophy and social movement which applies evidence and reason to working out the most effective ways to improve the world.”

—

To learn more about Singer’s philosophies visit his site TheLifeYouCanSave.org.

Let your voice be heard!