By

Kelsey

photo by Justin Ahrens of Rule29

I covet your faith. I’m not sure if that breaks any of the commandments or not. It probably breaks several. Still, I do.

My time with Life in Abudance was awesome for several reasons. One of them is that I had a chance to be around people with such strong faith.

I’m surely surrounded by others with such faith, but there is a separation of church and day-to-day life. I appreciate the separation. I don’t want others telling me what I should believe and I don’t want others telling others what they should believe. Religion and politics are in the “don’t go there” category for me. Unless I know someone is up for an honest and open discussion, I avoid them at all costs.

The last time I prayed, I think I was praying for a puppy dog. It’s been awhile.

Going into this trip with a Christian NGO, I knew that faith would be front and center. And at some point mine would be called into question. I wasn’t sure what to do. Do I stay in the closet and hope that I’m not called on to bless the food or share some spiritual insight? Or do I step off the plane, drop my bags and say, “The heathen has arrived” while making little devil horns with my fingers and flicking my tongue? Of course, I’m joking about the latter one, but honestly was I supposed to walk in and say, “I don’t have faith in Jesus like you do?” To me that’s like walking in to a room full of strangers and declaring who I voted for, or where I stand on abortion and gun rights.

Each night the group sat down and talked about the day’s events. These were deeply personal conversations. We talked about the children in the slums and when we thought of our own children it broke our hearts. Grown men were brought to tears (I’m looking at you Tonan).

But then they would talk about God and Jesus and about how what we had seen challenged and strengthened their own faith. That’s when I would go silent.

Gradually I was outted. Maybe it was when I dropped the quote: “To the hungry, food is God.” One of the team members pulled me aside and asked me, “Where do you stand on the whole faith thing?”

I answered honestly. I suck at being anyone else. And I was accepted. One of the team members said that he thought I was brave for coming on the trip. It really didn’t concern me that much. I’ve lived with and traveled with folks whose cultural and religious traditions were far more greater than my own, including Buddhists and Muslims. I was raised catholic - an altar boy in fact - and like to think that I shared the values and concern for the poor that all the others in the group did. We just had this one thing that we didn’t share. I relate to Jimmy Buffett, a former altar boy too, who now claims to be an altered boy.

I prayed more in that week in the slums of Nairobi than I have in any other in my life. The first prayer in the slums was led by Bruce, who is a pastor in Illinois. Along with two other team members we were crammed in a 10X10 shanty with a single mother and a few of her six kids. We bowed our heads, held hands, and Bruce began to pray.

By the time Bruce was done, my eyes were watering. It wasn’t some spiritual revelation that hit me, but it was just how beautiful and important prayer can be as a form of communication. We don’t sit down with strangers and loved ones alike and express how thankful we are for them, how much hope we have for them, and how much we love them. Heck, I don’t even think about those things myself nearly enough. The passion, compassion, and the honesty with which Bruce and later the other team members prayed touched me.

I didn’t mind the team members knowing about my faith, but I really didn’t want the families we visited to know. That’s when I was uncomfortable. Several times during my 24 hours in the slums, I was asked to bless meals. The first time I said, “I hear myself pray all the time. Why don’t we let someone else.” (Lying about praying has to be worse than coveting faith.) Of course, they insisted. Thankfully, I had learned from Bruce, Anna, Amanda, the Justins, Tonan, Von, Brian, Bob, Gus and Earnest how to pray.

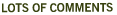

I want the poor to have faith that tomorrow will be better and if not tomorrow, then maybe the next day, and if not in this lifetime then the one after. The mother of the family I spent the night with was a “prophetess.” She saw a future that was a better life for her and her family. She was also bulletproof, but that’s beside the point. When I walk around the slums of Nairobi, I hope that others see a tomorrow that is better than their today. No, I pray they do.

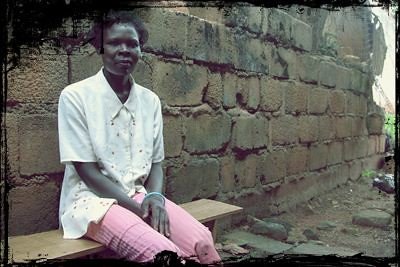

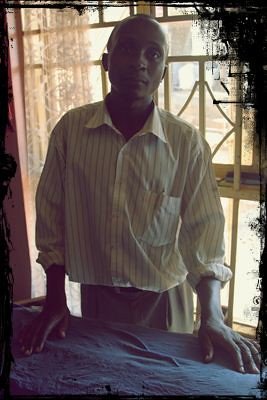

I was having a conversation with Justin, the US director of LIA, about some of these things and I mentioned how important I thought faith was for the poor. He misunderstood me and started talking about having faith in the poor. The poor possess ingenuity, a zest for life, a beauty that I can’t put my finger on, and great potential. That’s the saddest part of the slums. There is so much never realized potential.

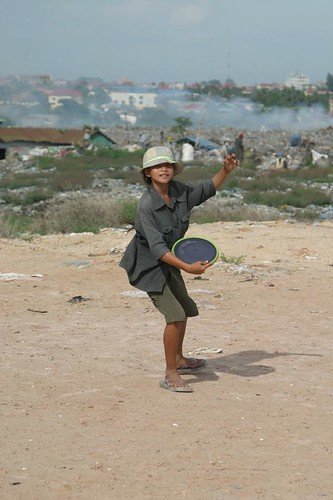

Von, a member of our group who is an artist, would start drawing and kids would surround him. One day he was armed with a bag full of notepads and gave an impromptu art lesson. One of the kids was amazing. Von saw his potential and slipped him a few extra notepads and pens. He must have told him to keep drawing 30 times. That day Von’s greatest fear was that this kid would stop drawing. Von has faith in the poor as every team member among us now has, if we didn’t have it before.

I’m trying to figure out poverty for myself. I’ve written a book on it and I’m still not sure how I feel about the conditions in the slums, the discrepancy between the haves and have-nots. The other team members turn to God to make sense of it. That must be nice.

I totally covet their faith.

I’m thankful for having shared this experience with them. They taught me that it’s important to have faith in the poor and for the poor to have faith.

Amen.

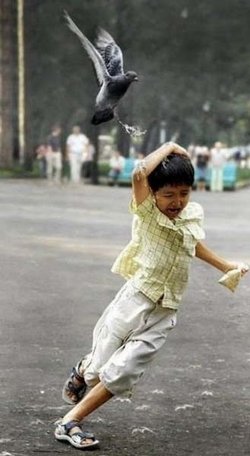

Unfortunately my superpower is summoning birds to swoop from the heavens and poop on my head.

Unfortunately my superpower is summoning birds to swoop from the heavens and poop on my head.

Digg

Digg Facebook

Facebook Flickr

Flickr LinkedIn

LinkedIn StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Twitter

Twitter